THE PANORAMA REPORT

Your phone is hungry for the world, hungry to consume everything in front of you. Regular images are no longer enough, we must survey, collate, stitch together.

Historically, the Panorama was patented by Robert Barker in 1787. A new type of image, different from the conventional still oil painting, the viewer of the panorama must move. Stephen Oetterman in his book The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium (1980) locates the Panorama as a novelty in the history of images. Its patenting places it alongside technical innovations of the 18th and 19th century such as the steam engine, automobile, and telephone.

While the panorama was largely a novelty, I want to stress the technical nature of this expansive image. Panorama’s were intended to be incredibly dense and accurate; only with a richness of information synthesised could the viewer be transported elsewhere through the image.

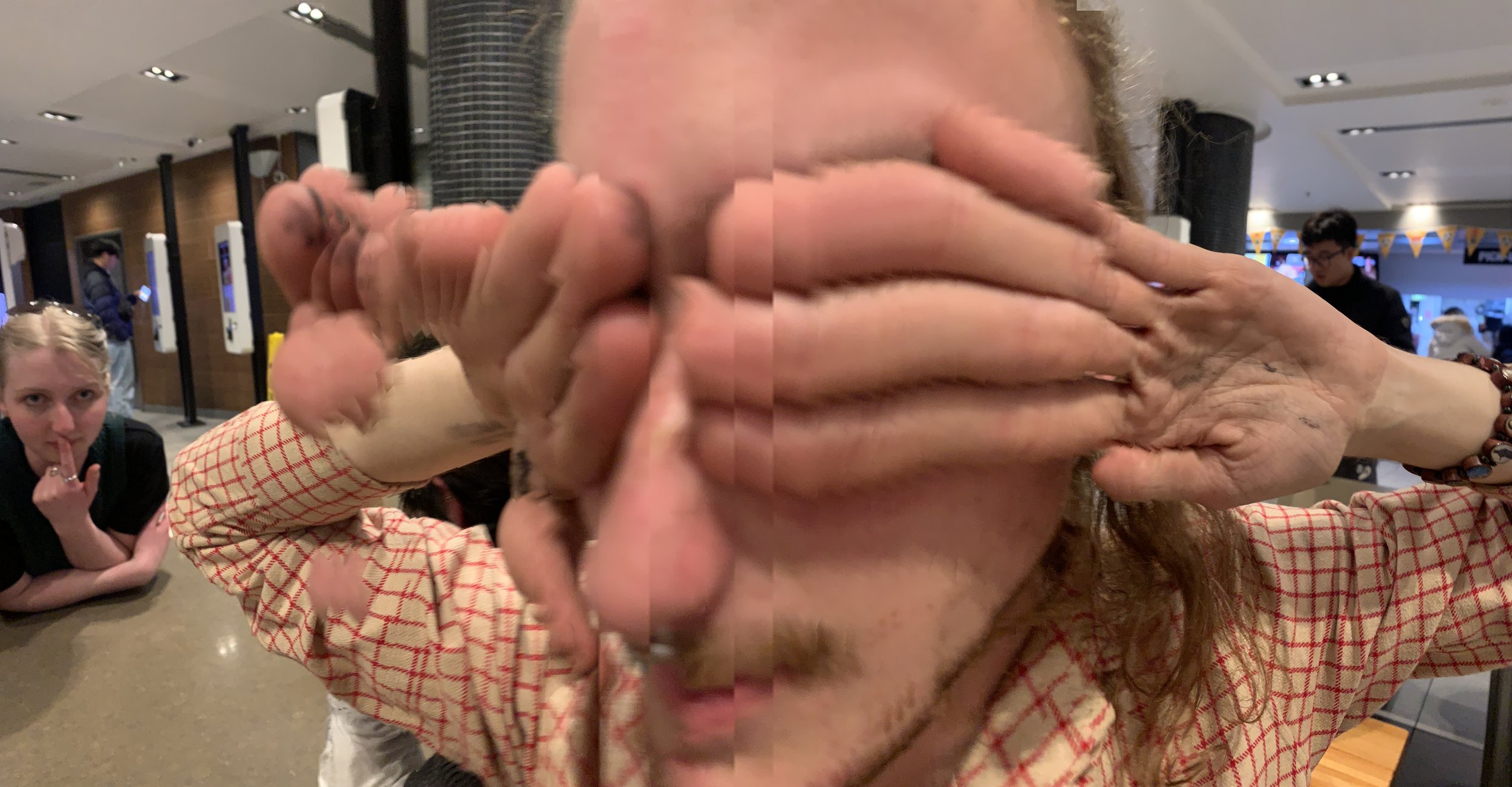

Realism and accuracy define the panorama as it occured in history. In its form the digital panorama contains the DNA of the informationally dense historic panorama, for the JPEG is a grid of values. However, the digital offers an inversion of this accuracy, stretching, glitching, clipping, and skipping details as the image algorithm tries to smooth out the jitter of my hands. These “breaks” in the digital image reveal the untruth and unrealism of its construction.

Your phone is hungry for the world, hungry to consume everything in front of you. Regular images are no longer enough, we must survey, collate, stitch together.

The panorama resists posting and being displayed. Irony of a form not even being fully viewable in it’s taking.

The hilarity of the vertical panorama, mirroring the ways we survey each other, looking one and other “up and down”