6 times The Untamed was like, “Censorship who?” and gave the gays their rights

Words by Jocelin Chan

By now, audiences are no strangers to queerbaiting. This much-condemned practice—or, more accurately, marketing technique—sees creators hint at queer romance in fiction but stop short of depicting it. The aim is to “bait” LGBTQI+ viewers into consuming the media in question without alienating more conservative audiences. But what if the situation was… reversed? What if creators wanted to but couldn’t depict queer relationships because of media censorship? What do they do then?

Enter the Untamed. This Chinese historical-fantasy drama follows the hijinks of the Wei Wuxian (Xiao Zhan), a cheeky young man who forms an unlikely bond with Lan Wangji (Wang Yibo), a strict rule-follower. They find themselves embroiled in political conflicts that result in Wei Wuxian being killed as an outcast, before he is resurrected sixteen years later to reunite with Lan Wangji and solve a murder mystery. The show is based on a webnovel (Mo Dao Zu Shi by Mo Xian Tong Xiu) and has one glaring difference to its source material: the Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji of the novel end up getting married. Produced in China with strict media censorship laws against the depiction of queerness, the show was forced to erase the more romantic elements of the protagonists’ relationship.

In spite of this impediment, the showrunners were undaunted. Many fans of the novel expressed surprise and delight at the lengths to which the show went to depict Wei Wuxian and Lan Wanji’s relationship in queer terms. For queer audiences with Chinese heritage, it is doubly important that such a large-scale and popular Chinese production has been so dedicated in preserving the queer content, instead of hetero-washing the whole adaptation. These representations affirm the place of LGBTQI+ people within Chinese culture. So, what does depicting a queer relationship look like in a censored media culture? Here is how the Untamed did it...

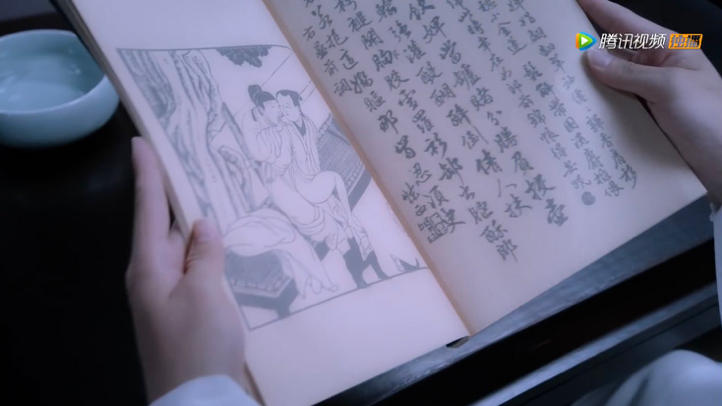

1. Gay pictures

It’s not banned if it’s art, right? The producers slipped in some cheeky ancient gay porn into a book that Wei Wuxian tricks Lan Wangji into reading and… somehow, that passed censorship.

Absolute kudos. This isn’t the only “gay picture”: in a later scene, Wei Wuxian wakes up in his bed and looks fondly at a drawing that (presumably) his younger self scribbled into the bedframe of two boys holding hands and kissing.

2. That headband

The members of the Lan clan sport a ubiquitous ribbon across their foreheads. As Lan Wangji asserts in Episode 6, this sacred headband represents restraint and cannot be touched by anyone except one’s parents or significant other. Thirty minutes later, Wei Wuxian has persuaded him to wrap the ribbon around both of their wrists as protection from a murderous zither (don’t question it). The implication, of course, is Wei Wuxian is that significant other. This isn’t the only time that Wei Wuxian touches the headband either; he pulls it off Lan Wangji to splint his leg and ties it back on, and playfully tugs on the headband when he possesses a paper figure to go undercover.

3. #justchinesecouplethings

Some of Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji’s interactions allude to traditions performed by Chinese couples. The most obvious allusion is to the “three bows” (or kowtows) of the marriage ceremony—one to the heavens and the earth, one to the parents (or “ancestors” by extension), and one to each other. During one scene, the pair meet a Lan ancestor and bow together to her; in another, they perform three bows before the funerary plaques of Wei Wuxian’s adoptive parents. In another scene, a drunken Lan Wangji tries to gift Wei Wuxian with a pair of chickens, alluding to the practice in which a man gifts pairs of chickens to his betrothed. The pair also gift a child with lucky money together, which married Chinese couples tend to do together.

4. Subtle kisses

Since censorship won’t let the main pairing kiss, the drama also declines to show its heterosexual pairings kissing (the single, one-second kiss in the entire drama has the dubious honour of going to a random old clan leader and his concubine). But the producers turned to subtler means too. Two rabbits, which are a motif of Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji’s relationship, bump their noses together in a “kiss”. Rabbits are doubly significant in Chinese mythology as a symbol of queerness; the Chinese god of homosexual relationships is called the Rabbit God. The showrunners also managed to slip in another kiss; Wei Wuxian blows a cheeky kiss to Lan Wangji when he possesses a paper figure.

5. Wangxian family

In perhaps what is its cutest scene, the drama goes at lengths to portray Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji in familial terms. At one point, Wei Wuxian becomes caretaker to an orphaned toddler called Wen Yuan. On one of their excursions to the nearby town, A-Yuan runs off and clings to the legs of Lan Wangji who has come for a visit. A-Yuan starts to kick up a fuss and the townspeople mistake Lan Wangji as the child’s father, asking, “Where is his mum?” Right as they ask, the camera trains itself on Wei Wuxian. The townspeople’s error is cemented when Wei Wuxian jokes that he “gave birth” to A-Yuan. Lan Wangji’s does in fact become A-Yuan’s adoptive father later on, reinforcing the depiction of the pair as A-Yuan’s parents.

6. Queer-coded vibes

In general, the entire vibe of the drama suggests that queerness is not unique to Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji’s relationship. This is mostly conveyed through queer-coding basically most of the characters. Queer-coding is a neutral term that refers to certain traits or behaviours in characters suggesting that they are not cisgender/heterosexual. It has gained a bad reputation through Disney’s notorious penchant for queer-coding villains (cf. Jafar and Ursula), but the Untamed avoids pairing queerness with evil by essentially queer-coding everyone—from the fan-toting Nie Huaisang to the brusque doctor Wen Qing, the seemingly-inseparable Xiao Xingchen and Song Lan, and the amoral and giggly Xue Yang. Besides the relationship between Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji, the drama portrays the relationship between Lan Xichen and Jin Guangyao in romantic terms, replete with lingering gazes, protectiveness, and dramatic displays of devotion.

The Untamed ultimately portrays a world that feels like queerness is a norm, even if it must fall short of actually depicting queer relationships because of Chinese censorship. The dedication that the producers put into staying faithful to the novel is hopefully signals the beginning of a journey to greater acceptance of portraying LGBTQI+ themes in Chinese media. Certainly, the Untamed has won millions of fans worldwide, reflecting how receptive audiences are to queer themes. On a cultural level, such stories challenge the state narrative that queerness is antithetical to Chinese traditions and values. For LGBTQI+ Chinese viewers, this is such a landmark in representing and accepting their identity.