Do Humans Dream of Mammalian Sheep?

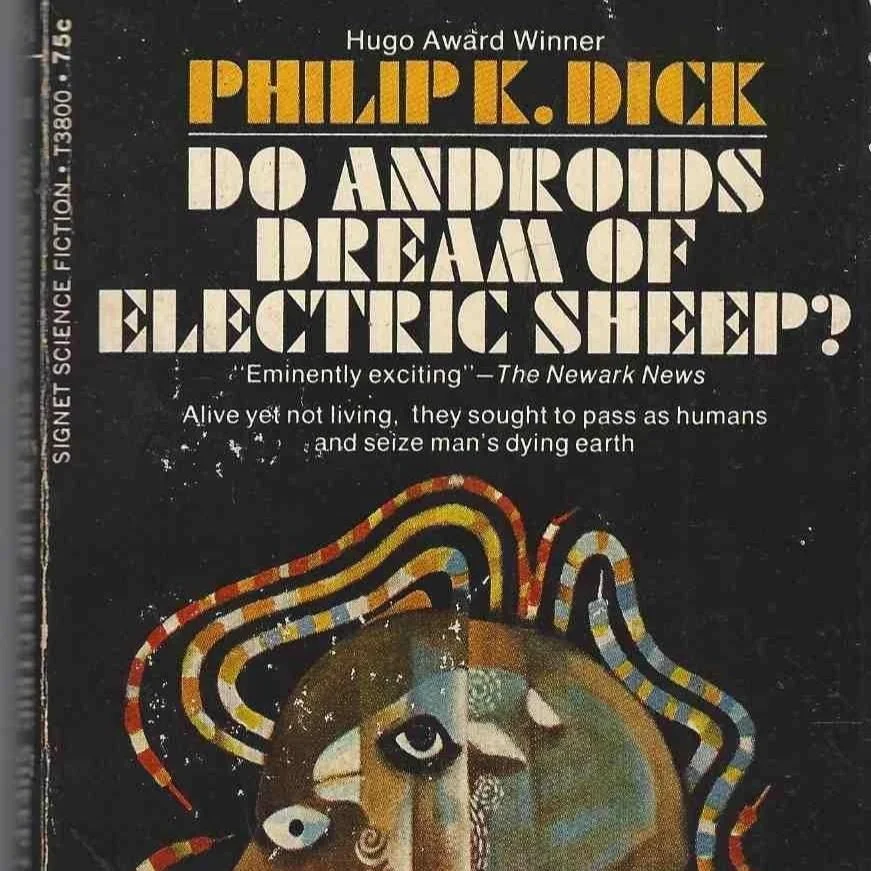

Philip K. Dick, Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? (1968)

Call me a luddite if you must, but these days I have been feeling borderline Kazscynskian towards anything that passes the Turing test. To me, it is becoming clear that humanity’s intellectual capabilities will soon be rendered obsolete by artificial intelligence.

After the industrial revolution, we lost the ability to be at one with nature; we lost our connection with our labour, and our bodies. As Silvia Federici notes, bodily alienation was a defining feature of capitalism. We reviled humanity’s ‘natural state’ to lengthen the working day, overwhelming the body’s natural limits. With a Cartesian split, the mind became the realm of temperance and prudence, while the body became the machine and the source of libidinal evil; brutish and distinct from the rational faculties of the mind. [1] Despite our bodily alienation, the ideas we had and shared were still distinctly our own.

In our age of technological (dis)enlightenment, this is no longer the case. Half of the work produced by university students is the haphazard copy-and-pasting of spit from chatbots, alongside corporations’ usage of image generators for AI ‘art.’ In the final throes of late-stage Warholianism, it seems that people can no longer come up with ideas on their own without the safety wheels of ChatGPT.

In the days of Aristotle, humans were distinct from animals because of our minds. But AI systems process information, recognise patterns, and generate outputs in a way that reflects the human mind. Yes, this is an artificial mimicry and not consciousness per se, but does this distinction matter if we cannot tell the difference?

We still don’t really know how consciousness works. Biological essentialists in the USYD psychology department with positivist outlooks would probably say that, cognitively, we are no different to a machine. Except the machine is more effective. It hallucinates today, but one day the heuristic thinking of humans will be inevitably patched out.

But it is these heuristics—the disjointed jumping of ideas, chaotic and inefficient and unexpected—that that allows us to make art and makes us human. What will the world look like with the chaos patched out of it? At a time when machines can conceptualise the idiosyncrasies of human life, eerily mimicking the idiosyncrasies of human thought, we must ask ourselves: what sets humankind apart?

At least for now, AI is not embodied, it does not know love, it does not know lust or hate or fear. It does not know the fear of death, nor does it know the warm embrace of a drunk cigarette (or three). It does not know the feeling of dirt. Taking the question posed by the title of Philip K Dick’s novel Can Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), we should ask ourselves not if androids are dreaming of the electric, but if humans can still dream of the humble mammalian sheep.

Think of what the humble sheep symbolises: earth and dirt and wool and mud and grass and hunger. Warmth and blood, purity, the body; vulnerability. Something warm-blooded. Something real.

Riddled through the passages of Psalms, sheep were once biblical and pastoral, innocent and pure. Now think of the electric sheep. If you’re anything like me, the most encounters you have with animals these days is in the form of Instagram reels of horses and sheep frolicking in a field with Bladee in the background. A synthetic simulation of the real. Hollow but functional. Manufactured contentment, an ultimate collapse of meaning.

As Isiah 53:6 condemns us: “We all, like sheep, have gone astray; we have turned every one to his own way; and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all.” [2]

We rarely encounter animals these days; we are deprived of the farm. When was the last time you saw a mammal up close? Not a cat or a dog, but something big and bovine. There is something awe-inspiring about being up close to a cow, or even a sheep, creatures so big and strong that they could literally kill you if they wanted to. Driving past cows is like coming face to face with the sublime.

Whether the artificial writer, artist, or white-collar worker is a pale imitation of the real thing or even a worthy creator themselves does not really matter. Humans may very well soon be rendered obsolete either way, by a creature of our own making, much like God and man. Soon we will yearn for a bygone era when we didn’t have these debates, where we could just create freely and wallow in dirt that still had worms in it.

If AI can mimic our mind, the thing that sets humanity apart is the body. We must affirm the biological, the physical, the muddy and the messy.

In true luddite fashion I fear we are slouching towards a digital dystopia. In a thousand years androids will probably dream of electric sheep in bits and ones and zeroes.

But right now, while human-generated intelligence still has a foothold, we must act. Can we still dream about the real; or are we too entangled in the synthetic to notice the difference? We must affirm the body; we must exalt our natural state. Otherwise, we will be sidelined by a digital monster of our own making; dreaming of the past and of mammalian sheep.

[1] Federici, Silvia (2004). “The Great Caliban: The struggle against the rebel body.” Capitalism Nature Socialism 15(2): 7-16.

[2] Bible Gateway (n.d). “Isiah 53:6.” New International Version. Available from: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Isaiah%2053%3A6&version=NIV