The pulse within these threads

These threads remember the life and the fight of the people forever.

There’s resistance within these threads.

There’s love within these threads.

There’s hope within these threads.

There’s life within these threads.

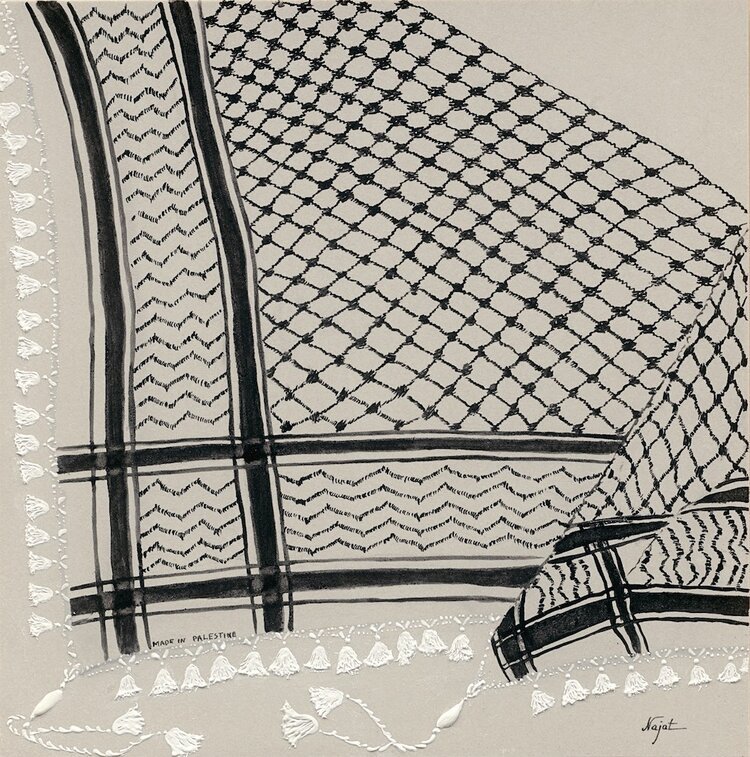

Image credits: ‘Kuffieh 3’ by Najat El-Taji El-Khairy

These stitches crisscross and flow with stories of the people; the love and the history they created. This fabric holds the labour of the farmers who weaved it and the care of the woman who threaded art into it. This fabric is draped on the people who create life and fought against those who tried to take it. These stitches remember the resistance and the fight among the people who wore them.

The life and the fight will live within these threads forever.

The rich tradition of Tatreez (تطريز, Palestinian embroidery), finds its origins in rural areas in the 1800s, eventually evolving into a widespread practice across the region and among the diaspora since 1948. Initially tied to rural attire, embroidery now permeates Palestinian culture, showcasing the intricate beauty of its heritage. This art form was passed down for generations — mothers would teach their daughters, one needle and thread at a time, to string mosaics of colours and shapes into various garments, to create pattern combinations that tell a different story about land, belonging, love, and resistance.

The traditional Thobe, a loose-fitting robe, is one of the main canvases for the art of Tatreez. Decorated with detailed embroidery, this clothing is hand-stitched with arrangements of threads and symbolic motifs. Some designs lean more towards abstract geometric shapes such as chevron or the eight-pointed stars, which was often used for identification of village background. Other symbols were pulled from the flora and fauna of the land, such as the cyprus, palm tree, or most popularly, the embroidery of S-shaped leeches given their use to heal the sick in ancient medicine. These traditional patterns often communicate something about the woman wearing them. They reflect various facets of her personal identity — social status, regional identity, marital status, and even economic status.

Tatreez has always been about the land and from the land. Not only does the embroidery hold symbols of nature such as the blossoms plains of Bayt Dajan, but fabric dyes are also derived from natural items such as grape leaves and pomegranate skins utilised from the land surrounding Jaffa. For instance, red dye is produced from common native plants like madder and insects including kermes and cochineal. Blue dyes come from the commonly found Indigo plant in the Jordan Valley, which was used to produce many nineteenth and early twentieth-century dresses to ward off the evil eye. The use of red, purple, indigo blue, and saffron reflected the ancient color schemes of the Canaanite and Philistine coast. The Islamic green and Byzantine black were later additions to the traditional palette.

Much like the Thobe, other famous Palestinian garments have deep historical roots to the land. The Keffiyeh, a traditional headdress originates from the country’s Bedouin communities and local farmers.They were originally used as a practical garment to protect wearers from the harsh desert environment. The garment is woven from lightweight cotton and blanketed in symbolic imagery: fishnet patterns representing the connection between Palestinian sailors and the Mediterranean Sea; bold lines signifying the trade routes that go through Palestine; and intricate leaf patterns mirroring the resilience of the olive tree, which serves as a representation of the Palestinian people's rich identity, culture, and unwavering spirit.

Image credits: ‘Cross Stitch Sampler’ by Najat El-Taji El-Khairy

Palestinian Tatreez and garments have been an important form of resistance and political expression for centuries. In 1948, at the end of the Arab-Israeli war, the withdrawal of British forces resulted in Israel declaring independence and engaging in war with Palestine. This led to the mass displacement of Palestinians, or the Nakba (النكبة) meaning “catastrophe”, where an estimated 700,000 people fled or were expelled from their homes. With a large segment of the population forcibly displaced from the region, the Nakba dispersed and fragmented the growing fashion sector and every other element of Palestinian society. Hundreds of Palestinian towns were depopulated, and thousands of Palestinians lived in refugee camps. What was once a communal practice that allowed Palestinian women to embroider garments for themselves and others became an abandoned luxury due to constant displacement alongside a lack of time and supplies.

Similarly, much like Tatreez embroidery, the keffiyeh has a long history of being synonymous with Palestinians and their demands for sovereignty. During the British mandate of Palestine, rebels and revolutionaries often wrapped the keffiyeh around their faces to avoid identification and arrest. Yet, when the British banned the scarf, as a national protest, most Palestinians began wearing it to make the identification of rebels impossible by the authorities. During the 1970s, the keffiyeh gained prominence when Leila Khaled, a revolutionary freedom fighter and member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, wore it as a headscarf and encouraged Palestinian women to do the same, fostering a sense of solidarity. It was worn most famously by Yasser Arafat (former President of the Palestinian National Authority) when he addressed the UN General Assembly. Continued importance was gained during the Intifada in 1987 and again during the Second Intifada in 2000 when people in Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, and Yemen wore the scarf to show solidarity for Palestinians against the Israeli occupation. Worn by Palestinians and their global allies, this iconic scarf serves as a tangible expression of unity and resistance against oppression. Its core significance remains deeply rooted in the preservation of cultural heritage, the promotion of awareness, and the cultivation of a collective identity shared by Palestinians. As people around the world protest for the rights of Palestinians living under constant attacks from Israel, they donned the keffiyeh — a symbol of Palestine.

The visual language of the practice changed, resulting in Tatreez patterns becoming simpler. Various patterns and imagery were lost over time and their meanings displaced. One of the main reasons behind this includes environmental degradation caused by increasing settlements, meaning that some local symbols and iterations of Tatreez patterns are now extinct in tandem with over 400 villages that have been ethnically cleansed. Still, many women continued to wear their thobes or carry them on their backs as a statement of the continuing existence of the villages they had been expelled from or became extinct. Today, Tatreez patterns are worn by people in the diaspora, becoming a symbol of Palestinian identity, heritage, and displacement.

Palestinian women continue to create radical roots utilising artful Tatreez embroidery techniques and fashion to push against Israeli occupation. During the occupation, the women would at times stitch escape routes that protestors facing the occupation army could rely on to survive. In 1967, when the flying of the Palestine flag was banned by the State of Israel, women began embroidering the flag and its colours through their clothes as a sign of resistance, this was identified as the ‘Intifada dress’ .

Although much of the organic practices of garment making and Tatreez embroidery have faded over time due to the genocide in Palestine, attempts to keep these practices and stories alive remain. Over the years, these practices have become an important source of income and independence for the diaspora, especially in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon where many Palestinians are banned from various professions. A few formal training centers are attempting to develop and survive to provide displaced Palestinian and Syrian artists a space to teach the practices of Tatreez. This also helps the artists financially gain freedom but also to take part in preserving the stories that are being lost.

In 2021, UNESCO added Palestinian embroidery to its list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, recognizing it as “a widespread social and intergenerational practice in Palestine,” a symbol of nationalism. Following the development, The Palestinian Heritage Centre in Bethlehem inaugurated a Textile Conservation Studio to preserve Palestinian thobes and other heritage fabrics and to provide training for conservation and restoration.

From the river to the sea, one day Palestine will be free. And the woman of the land will come together once again to weave art and love into the fabrics. To create new history and bring the flowers of the land back to life. To pass down the story of resistance, of strength, and of love to the children who listen. Until then these threads hold the remembrance of Palestine and its people. These threads remember the life and the fight of the people forever.