Curating the doctor’s waiting room

What were the curatorial decisions that went behind the art in the doctor’s waiting room?

Image Credit: Bonnie Huang

Co-written with Harry Gay

You’re sitting on a chair. It could be soft and lumpy, or hard and stiff. Incandescent lights shine above, bathing you in a harsh glow that stretches time to infinitum. Is it day or night outside? Who could say? The garish carpet fills your periphery. The receptionist said it wouldn’t be long. The last time you let your gaze direct itself at the clock, it had been 20 minutes. You let your eyes wander. First at your shoes, then an awkward glance at the person sitting diagonally from you. Their eyes meet yours and your pupils quickly shoot elsewhere. The only place to look is directly in front of you. There, hanging on the wall, is an artwork.

We’ve all been in waiting rooms at one time or another. Whether it be to get our teeth checked, a COVID swab, a lip filler, or a spinal adjustment; anyone and everyone has had to sit and wait for their body to be pried, inspected, and examined all over. The waiting room is an uncomplex space. A place to put those who are merely waiting to get from one room to another. It is usually deemed the most insignificant part of any visit to the doctors, dentist, or what have you. For people who run these establishments, all they really had to do was stick a couple chairs down and they’d be done. Instead, they also chose to hang works of art.

In doing this, they bridged the much maligned chasm between science and the Arts, and became art curators in their own way. As such, it became our duty to adopt the personas of art critics, to investigate and analyse the reasons behind these choices. What were the curatorial decisions that went behind the art in the doctor’s waiting room? Does one type of waiting room differ from another? These are the questions that have plagued our minds recently, and having been in and out of doctors offices our whole lives, we’ve had a lot of time to ponder these questions — and a lot of time to wait.

A psychologist's office tucked away in the Warringah Mall Medical Centre houses a series of abstract works that line their halls. Splatter paintings loom larger than life over patrons as they sit in their chairs. Perhaps the doctors really liked Jackson Pollock, or maybe it was an evocation of the complexities of the human mind.

Image Credit: Bonnie Huang

A nearby doctor’s office plays host to a series of miscellaneous works by different artists. Printmade flower work of muted greens and yellows are juxtaposed against the vibrant colours of nearby etchings depicting romantic scenes from classic literary works such as Alice in Wonderland and A Midsummer Night's Dream. Old sepia photographs of Sydney stand opposite a Brett Whitley inspired view of the Harbour Bridge, and just round the corner, larger than life dot paintings. What begins as a trip to the doctors, turns into a complex reimagining of the nation and a confrontation of our colonial history, with cultural imperialism trading out Indigenous works for ones by British authors.

At a medical centre inside the Sydney International Airport, a lone abstract art piece sits isolated on the stark white wall. The space is small and compact and, suitably, so is the work. This geometric art is two-dimensional in form, flattening out and subverting notions of spatiality, merely depicting a circle and two squares. Its location at the airport symbolises the ways in which aeroplanes figuratively flatten and eradicate space and time, transporting individuals from one nation to another in a matter of hours.

An orthodontist in Balgowlah is very postmodern in its curation. Blank empty walls, save for a series of before and after photos of teenagers’ teeth, and a video work depicting the benefits of Invisalign. The orthodontist is clearly suggesting that they are a business that embraces new technologies in the age of the digital. Rather than the doctors, who use classic modes of art such as paintings to cement their profession as something traditional and reliable, the orthodontists are high-tech, cutting edge, and pushing the boundaries.

In the CBD, a pathology lab near Pitt Street is entirely bereft of art. A bold choice that leaves these writers scratching their heads. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a pathologist is “a scientist who studies the causes and effects of diseases, especially one who examines laboratory samples of body tissue for diagnostic or forensic purposes.” Perhaps their lack of art is a symbolic reflection of the ways in which they extract analysis from things invisible to the human eye.

A few streets over is a cardiologist, located 30 floors up in a skyscraper. Attempting to go up the elevator, it became apparent by the construction workers moving in and out that there was no way up. Defeated and trying to think of how the inability to get to the cardiologist related to the article, it suddenly became evident that a foyer is also a waiting room, medical-related or not. Inside this ground floor level hangs a large rectangular sculpture, in which its odd shape stood out from the surrounding charcoal marble. Despite having a mirrored surface, it was designed to be crumbled up, so as to reflect nothing at all. This is fitting, as in the corporate world of people in suits moving in and out of these monolithic buildings, they show no reflections and are merely capitalistic vampires. Maybe that's why there was no access to the cardiologist, because the blood was drained from its vessels long ago.

Image Credit: Bonnie Huang

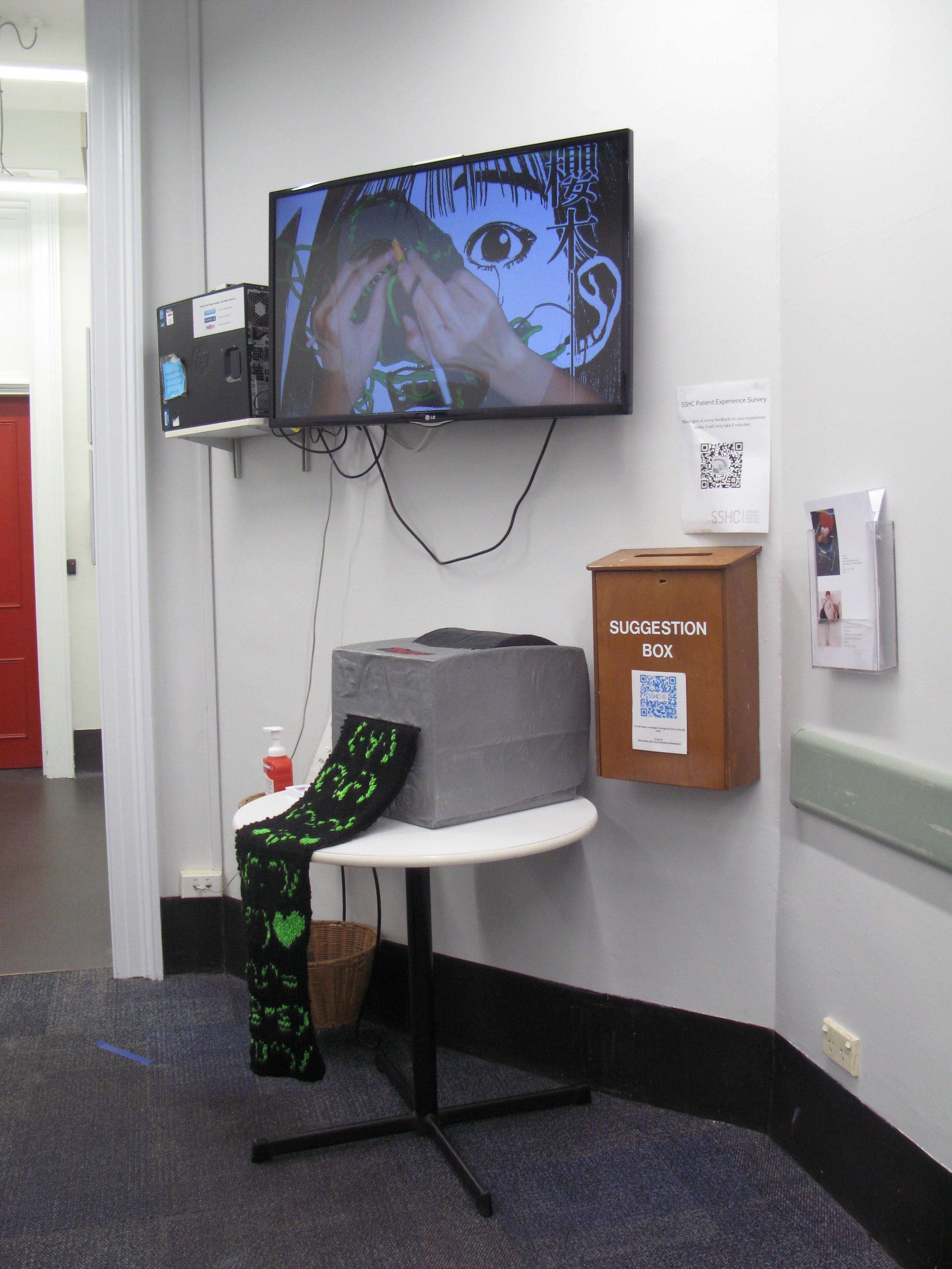

Recognising the curatorial potential of the waiting room, the Sydney Sexual Health Centre (SSHC) accommodates an artist-run exhibition space in the waiting room of the clinic. Wedged in-between The Domain and Martin Place, this liminal space becomes one of opportunity. Among evenly spaced red and blue chairs with stainless steel framing, artificial grass sprouts from the carpet, hairs grow from white canvases that blend into the walls, beaded cobwebs become curtains against the window, and fuzzy creatures sit themselves across the room.

Since its founding under the leadership of Upasana Papadopoulos in 2018, The Waiting Room Project has presented monthly exhibitions featuring local conceptual and experimental artists from diverse backgrounds.

The current show and the second instalment of their 2022 program is Waiting For Black Dahlia by Amy Meng, a fibre-based interdisciplinary artist. Her work surveys the connection between kawaii culture and Surrealism through a psychoanalytic perspective.

Here, the artwork has been purposefully curated to change the way waiting room spaces have traditionally been occupied, alleviating some of the anxieties that can manifest when sitting on sterile and uncomfortable clinic chairs. The four caretakers emphasise the importance of retaining the functionality of the space, while simultaneously disrupting its monotony, forming a more “intimate” social, emotional, and mental “connection with the waiting room and its occupants.”

According to their website, “the art reimagines and transports artists, curators and visitors alike to worlds far beyond the hospital.”

“Being both the SSHC and a non-white cube space, it’s more than often occupied by marginalised folks, and we aim to reflect these same communities and idenities through the artists and artworks to curate a space that is inclusive and conversational at its core,” say Sehej Kaur Sehmbhi, Sarvika Mishra, Kaylee Rankin and Melanie Raveendran, the current caretakes of the space.

Reflecting on the feedback received through written and verbal surveys, visitors have expressed experiences of “meaningful interactions with the art resonating with the space and leaving with an intangible yet imperative sense of feeling seen, heard, accepted, and valid.”

Whether purposefully curated, or by chance, art on waiting room walls provide a space of reflection that cannot be found elsewhere. Unique to the space, there is a sense of anticipation and anxiety. The art in waiting rooms has the capacity to provide solace and escapism for patients, whose eyes often dart around looking for something to stare at. The next time you find yourself in a waiting room, take note of the work around you. More thought may have gone into it than initially expected.