Nuclear war? H’uh! What is it good for?

They wade through flooded towns in gas masks and hazmat suits, unable to breath in the toxic miasma of a sepia-toned world.

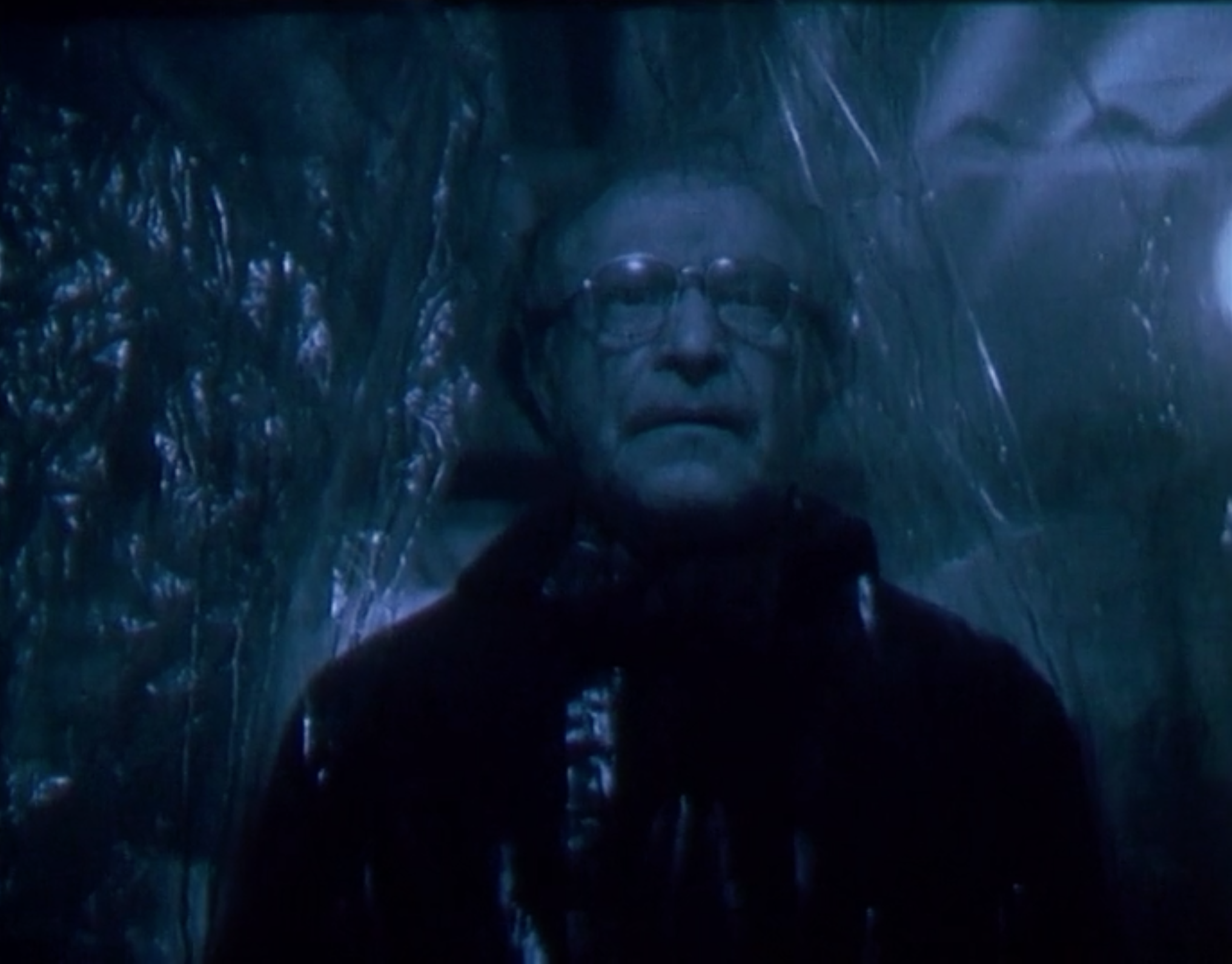

Image Credit: Lenfilm

With the amount of filmic representations of atomic bombs, it is easy to forget how truly terrifying a nuclear detonation can be: not just the people it kills or the buildings it destroys, but for those who manage to survive.

Radiation of a high enough roentgen destroys the human biological structure by smashing through the atoms that form our DNA and genetic code. The effects of this lead to cell mutations, the body burning to exposed areas inside to out, and all types of cancers, macules, papules, raised plaques of thickened pigmented, or ulcerated skin.

Beyond the body, a nuclear attack would most likely result in a nuclear winter: a phenomenon wherein the firestorms of a full scale atomic war result in the darkening of sunlight. As a consequence, intense wide scale cooling and reduced plant activity would result in crop failure. Global famine could follow suit.

Pandemics with diseases such as typhoid, tuberculosis, polio, and pneumonia, to name a small few, are expected to be rampant due to: sewage no longer being properly treated, crowded living spaces, poor food and living standards, and no vaccines. After all this, the global population would be predicted to drop below Medieval levels, with approximated early recovery to take at least 10-15 years, and a full return to our current population not expected for hundreds.

Amid the height of Cold War tensions, films from both the East and the West captured these horrors and anxieties in a gritty and realistic way: none more than Konstanin Lopushanksy’s Dead Man’s Letters (1986). This science fiction film is an overly dreary and miserable work from Russia, which depicts the aftermath of an atomic fallout on both individuals and society at large.

In this Tarkovsky-esque apocalyptic nightmare, the atmosphere of nuclear holocaust is filled with such empty hopelessness. Characters languish in underground tunnels, coated in their own filth. Exiting into the world and scavenging for scraps, they wade through flooded towns in gas masks and hazmat suits, unable to breath in the toxic miasma of a sepia-toned world.

Our protagonist, Professor Larsen, writes letters to his missing son, who we know is deceased: a hopelessly fatalistic task. A flashback reveals Larson active during the ground zero of when the bombs were first dropped trying to enter the children’s ward of a hospital his son is supposedly at. The ear-piercing screams and cries of children can be heard as he runs down the corridor, intercutting his horrified expressions with extreme close-ups of real-life footage of bodies being operated on and skin being torn apart.

Dead Man’s Letters prognosticates on what life in a post-nuclear apocalypse would be like in a realistic and existentially horrifying way, emphasising not only the manner in which atomic bombs destroy the body, but the world around us.